Ruins

It’s been more than a month since I posted. Rome seems full of detours. You set off on a course, but find yourself turned around or taken in other directions. Small misdirections or slight turns become changes of course, and so you end up somewhere else altogether from where you had planned.

Artists from the United States who visited Rome used guidebooks that directed them to the best sites - artistic and archaeological - to visit. Not dissimilar to more contemporary travel guides, these aids offered travelers lists based on what should be seen, and what could be missed. The art of antiquity and the Renaissance were the go tos. These guides were holistic: they included information on where to stay and eat, creating an entire travel experience for their readers. The most well-known of these guides was the Baedeker Guidebooks. These promised to “accompany the reader” on their travels and guide them through, every step of the way. These guides used a star system - from 1-3 - that demonstrated the significance of a particular site or monument. Readers could then making informed decisions about where they wanted to visit, guided by the editor’s judgement on a particular place’s relative importance or historical value in the context of its location or period.

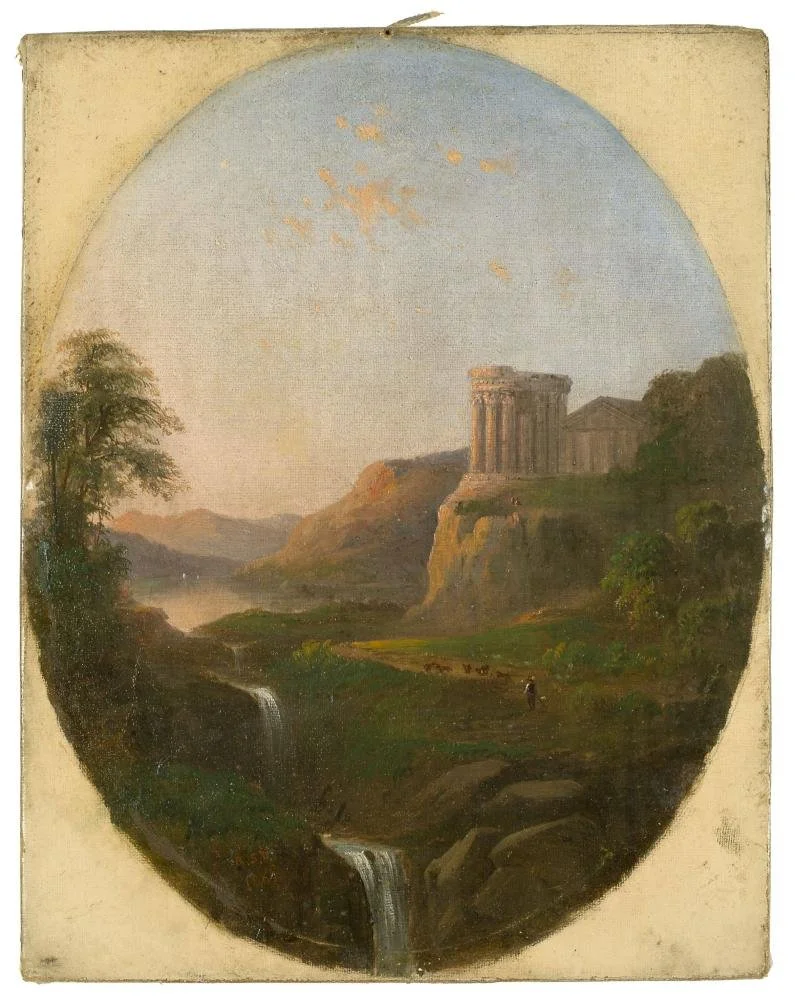

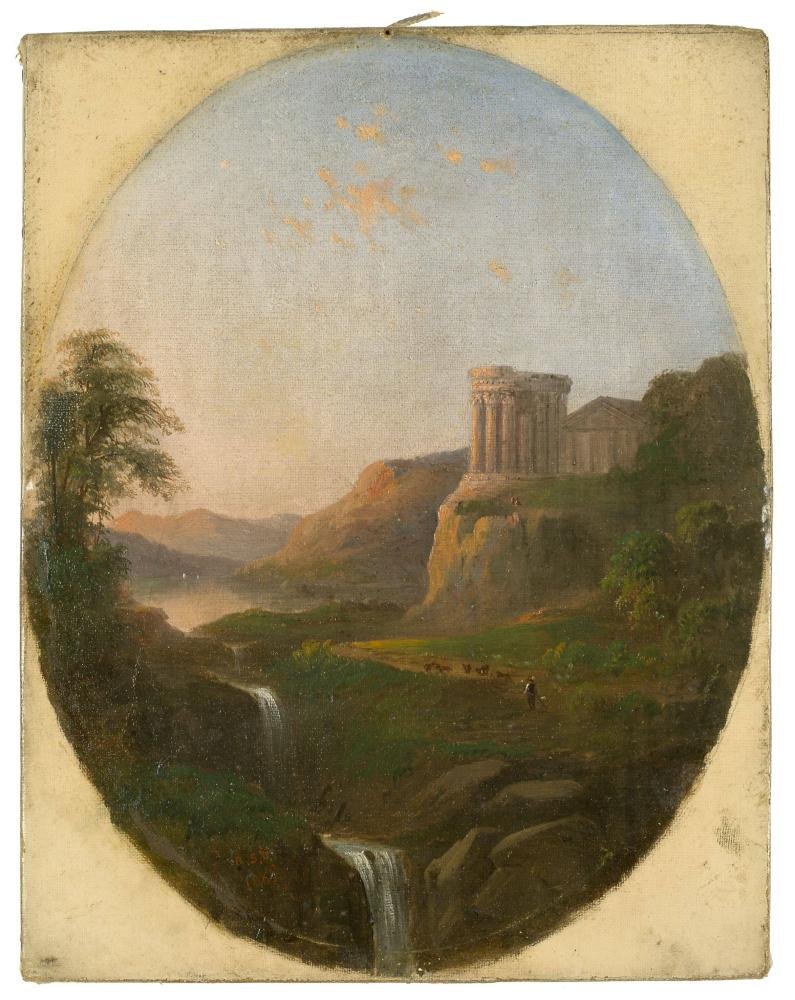

Robert Duncanson must have traveled with a guide book, and so he most likely already had a list of places he needed to visit. David Dorr for example opens his chapter on Rome with a description of a visit to the Vatican - the Holy City. He seems extremely interested in the way these catholic sites are built over, or adaptations of, the ruins of ancient roman structures. Certainly then, Duncanson must have visited the Vatican and perhaps he also, like Dorr, was interested in what had been there before. Dorr quotes from contemporaneous writers and guides, using their anecdotes to add context to the areas he is visiting. So many of Duncanson’s paintings of Italy are taken up with classical ruins, as well as what looks like later, medieval-era structures. For travelers in nineteenth-century Italy, for men like Dorr and Duncanson, the continual emergence of the past in the present must have been striking. Although some of Duncanson’s paintings name their location, several of them seem to be composites. Ruins of temples, columns, ancient foundation stones, palazzos in disrepair - structures he probably saw a lot of as he traveled through Italy. Their inclusion in his work is certainly atmospheric, evoking grandeur and reflection, but they are also subjects in their own right: monuments, moments and visual cues that ask for our close attention.

Because, right now, we don’t know much about what Duncanson saw or thought about what he saw, I’m trying to use David Dorr’s narrative along with Frederick Douglass’s description of his time in Rome to consider what Italy, and its antiquity, might have meant for an artist like Duncanson. But there are differences between Dorr’s, Duncanson’s and Douglass’s period eye and to me that lies in the nature of the ruin. Duncansons’ paintings are full of ruins. While Dorr and Douglass certainly visit ancient Roman sites, they use them to tell a story about Rome’s ancient grandeur. They are interested in evoking these historical societies from the structures they have left behind, describing the ancient residences of Augustus or imagining where the palace of Nero might have been. Duncanson leaves us with the ruin itself, nameless sometimes, but even when locatable, these are only remnants: broken architecture, stones and bricks, cracks and fissures, rubble, unfinished joins. These are what he leaves for our attention: places where the emergence of the past within the present seem particularly unfinished, moments of fractured time.