Dreams of Italy

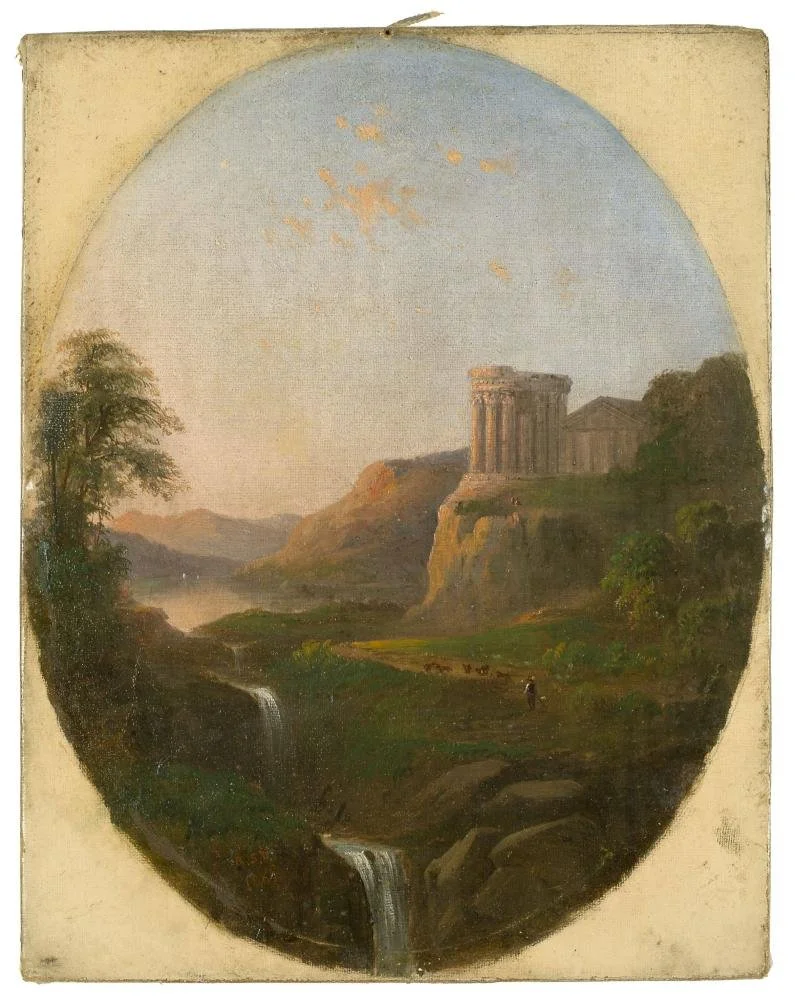

At first, when you look you might see soft light and shadowy foliage. Then you might notice the creamy pink horizon with its rose gold tipped mountain ranges that move down to embrace the glassy sea. From here you could move further out and walk among greenery and burnt umber, run your hands along stacked columns or broken down walls, wander amongst bushy shrubs, pause by a reflective pool, while earthy peasants watch you, and their playful grazing animals. If you look further into the background you’ll see what looks like an aqueduct and a shoreline settlement. Boats sail along the water in the mid ground, while a pilgrim walks slowly around the lefthand side of the composition towards a circular, walled structure.

Despite the stillness of this painting and its repeated invitations to reflect, the composition is full of movement. First there are the paths that take you across water, from one stage to the next, from the peasants in the foreground to the mountains in the background. Then there’s the constant sense of moving up, from the broken stone base at the very edge of the painting to the white frothy peak that point up to the streaks of cloud in the sky. Those clouds connect the ruins of a city on the hill on the right with the trees on the opposite side, to create a rounded, harmonious composition, that encases and encircles us, the viewer, in this dream-like scene.

Because of this, it’s hard to know exactly where you are: the ruins don’t necessarily date or locate the scene. Instead they create a sense, an affective view of an Italy both in its past and perhaps also in its mid-19th century present. It is a dream, and it is dream-like, an imagined scene. Or perhaps it is more correct to say this is a landscape painting constructed with an invitation to imagine, an invitation to dream.

In 1853 Robert S Duncanson, the artist who painted this composition, embarked on his first voyage to Europe, conducting his own Grand Tour – a journey that had become a rite of passage for artists by this time. Duncanson would have been around 32 when he made the trip, and he traveled with another Cincinnati landscape artist called William Sontaag. From Cincinnati, the two would have first made their way to New York and then boarded a transatlantic steamer. Once in Italy they clearly spent a good deal of time traveling and making on the spot sketches of archeological and tourist sites, that they worked into paintings, sometimes years later. Several of the paintings Duncanson made about his time in Europe are imbued with a dreamy nostalgia - not dissimilar to what I’ve described above. Ruined temples, rustic peasants, roaming animals, compositions that encircle and enfold. All these compositional elements seem to materialize the feelings conveyed in titles such as A Dream of Italy or Recollections of Italy. These were places that lived on in Duncanson’s memory, and continued to animate his imagination when he returned to the United States.

Now, as I wonder through the streets of Rome, looking and sounding very much like a tourist, I continually wonder what Duncanson might have looked at, how he might have felt, whom he may have met during his time in Italy. Certainly in the United States his lighter skin colour gave him a certain amount of latitude when it came to travel. In Italy he seems to have continued this mobility: no doubt traveling within the already well-established network of US artists, writers and emigres living in Italy, and to whom his abolitionist patrons would have provided him with introductions. While Duncanson’s Grand Tour of Italy may have emulated those of other European and British artists, it would also have tracked the journeys of earlier Black artists - we know for example that Robert Douglass Jnr an artist from Philadelphia made the trip to Europe in the 1830s, and Michel-Jean Cazabon, a Trinidadian born artist who trained in Paris, also spent time in Italy in the 1840s. Imagine, then, that some of these well-worn artist routes around Italy - that we still travel and retrace - were being created, and re-created, by African-descended artists who, like Duncanson, traveled to expand their visual heritage and aesthetic skills.

Not long before Duncanson made his own trip, another African American man, who would also land in Ohio, called David F Dorr traveled across Europe, North Africa and what is now the Middle East. Dorr was an enslaved man, accompanying Cornelius Fellowes a plantation owner in Louisiana. Dorr arrived in Rome on March 28, 1852, and described his journeys in a fascinating travelogue called “A Colored Man Around The World.” It is acerbic and witty, a carefully observed description of the social mores and hypocrisy of whiteness. It is also a beautifully descriptive evocation of the many cities he visited that reflects his cosmopolitan coolness.

Dorr’s writing exudes an abundance of self-possession, that is also reflected by Duncanson in a letter to a friend Junius R Sloan in 1854 where he describes visiting US artists’ studios in Europe – a common practice amongst traveling artists and potential art buyers. Duncanson states: "I am disgusted with our Artists in Europe. They are mean Copiests. My trip to Europe has to some extent enabled me to judge of my own talent. Of all the landscapes I saw in Europe (and I saw thousands) I do not feel discouraged.”

Whatever Duncanson experienced in Italy, like David Dorr, he maintained a clear sense of who he was, and what he might become. And so, while his dreamy evocations of Italy tell us what he might have seen and what he valued, they also demonstrate his certainty and confidence - in himself - and perhaps they manifest something of his hopes, and the futures he believed that his art could make possible.