Looking for Time

Waking up to the early morning light in Rome is to awaken in gold. In my kitchen it falls across the parquet floor and onto the white breakfast bar in long, flat, beams so that everything is striped with light and shadow. Colours are lit up and darkened simultaneously, shapes expand into the negative space around them, reflecting the strangeness of the term. Everything seems sharpened and expansive, everything seems so clearly defined, so distinct, and still so seamlessly intertwined. Our eyes search out, of course, for relations between things - for compositional balance, for organising the elements of what we see into a clear visual arrangement, but looking out at Rome in these early morning hours, reminds me again that we see, so much, through the frame of what has already been described, already been seen, already been composed. The question then might be, what is it I’m looking for, as I open my windows onto the courtyard below, the palazzo next door, the city expanding into the horizon beyond?

I ask myself this all the time here, partly because we’re living in one of the most beautiful Institutions in the city, we’re perched on a hill and so everywhere I walk there are views - grand views - of the city, and because it feels sometimes that when I’m looking, I’m also looking at something I’ve seen or have expected to see before. Non of this makes it any less breathtaking. I could stand in front of fontana dell’Acqua Paola or up on the Gianicolo for hours, watching in quiet. But I ask myself this question because I want to see this city through the eyes of writers and artists like David Dorr and Robert Duncanson: what is it that they saw, wanted to see, expected to see? Whose eyes did they see through?

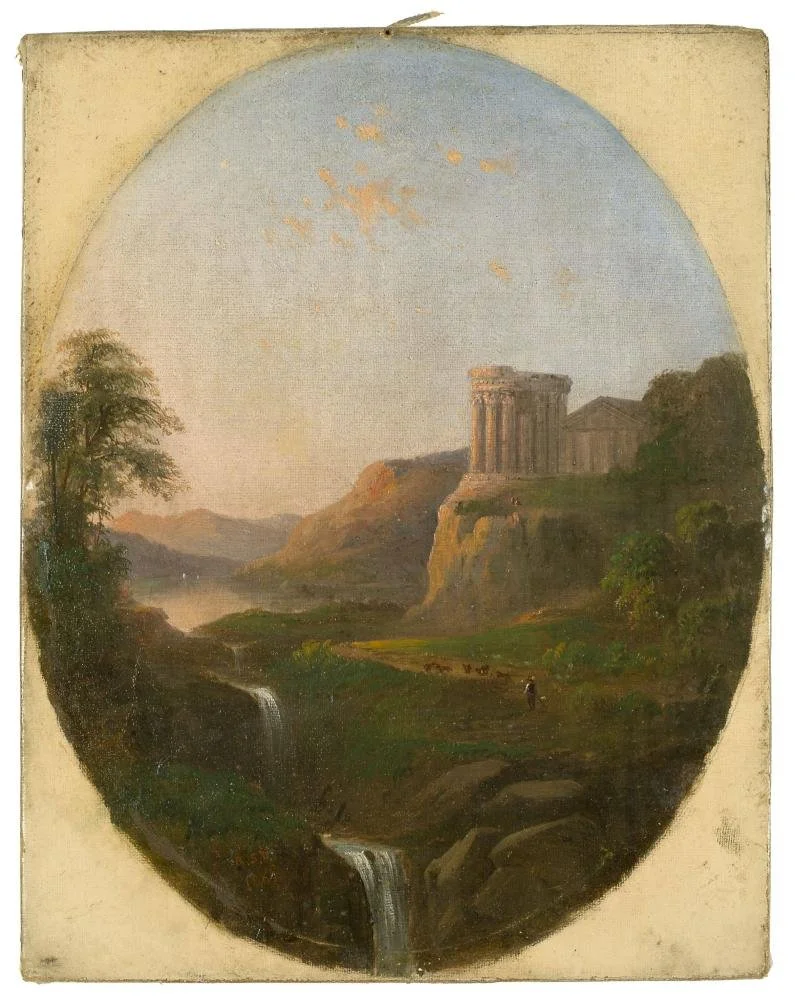

David Dorr for example populates his descriptions of various Italian cities with references to writers and archaeologists whose stories and excavations he uses as a way to both describe the past and remind readers that these pasts remain embedded in the present. For example his descriptions of Rome include excerpts taken from Cooper’s History of Greece and Rome and of North and South America, as well as a travel narrative written by a pilgrim and spy from the Middle Ages - Bertrandon de la Brocquiere. He includes their descriptions of the architecture that lies beneath the Forum and the stories they tell about the Tiber. Through Dorr’s eyes, Rome is a city built from the convergence of histories. I see this in Duncanson’s paintings as well, where Roman ruins and crumbling medieval edifices sit next to each other, looking over wildflowers and goatherds. Freud, famously, invited readers to imagine Rome like a psychical space, where past and present coexist simultaneously. The descriptions of Rome that Dorr and Duncanson leave us with also create this view, years earlier. And today, we are also often thinking about, and looking for, the ways the past emerges in the present.

Seeing the past and the present simultaneously was a viewing perspective also created in the vedute di Rome - popularised by artists like Piranesi, and widely circulated by the time Dorr and Duncanson were traveling through Italy. These views, and the visits of these men, also coincided with ongoing excavations in the city and in Napoli, as antiquity is recovered and uncovered. Clearly these travelers were also seeing Rome through these different perspectives: on the one hand the relative immediacy and oversight that came with tourist views and on the other hand the slow unearthing and fragmentary nature of archeological excavation. While they were clearly looking for, and finding, the past in the present (or maybe the past as the present), how did these different ‘tempos’ of visualising the city influence their descriptive practices? How did these tempos help them find what they were looking for?